Two-person exhibits in Ithaca are often ad hoc pairings. As such, it’s always encouraging to see two artists, strong in their own right, whose works elucidate each other’s through meaningful similarities and differences. Such is the case with the current “Summer Show” at Corners Galley in Cayuga Heights (it’s up through the end of August). Curated by gallery owner Ariel Bullion Ecklund, it features oil landscapes by local painters Suzanne Onodera and Stan Taft.

Onodera is a well-established artist, with gallery representation in California, Arizona, and Vermont as well as with Corners. “The Wild and the Deep,” her 2014 solo show at Corners, was a tour de force.

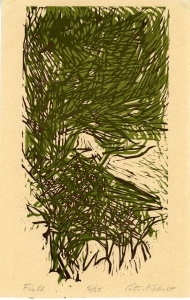

Her canvas and panel oils, often large, are abstracted landscapes: contemporary versions of the Romantics’ sublime vistas. While the classical European landscape offers the viewer places to stand, Onodera’s imaginary scenes transmute solid masses into ghostly liquescence. Her use of amorphous fogs and glazes, subtly accented with more visible brushwork, has been characteristic.

Onodera’s work here though has evolved, with her brushstrokes becoming thicker and heavier, with emphatically expressionist blocks of color standing out more against the thinly painted backgrounds.

A diptych on two upright canvases, Traversing the Steep Ravine is the largest piece here and the most overtly ambitious. Patches of acidic green—accented in bright yellow-orange and shadowed in black—help make it legible as a “landscape” but any sense of here-and-there is necessarily slippery. As in other pieces of hers here, a mountain seems to rise in the distance. Both the sky above and the river that winds its way down to our feet are in pale, softly brushed colors.

And Other Observations, a smaller near-square piece on panel, is just as compelling. The brushwork is brusque and broken while the palette combines the ethereal and the earthy.

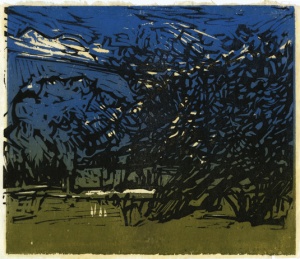

Stan Taft, a longtime professor of art at Cornell, has had two previous solo shows at Corners. His exhibit last year, “Tree + Landscape,” showed off something of his eclectic range as a painter. The “tree” series featured black silhouettes against fields of flatly painted, often lurid color. Subtler—and easier to digest—were his landscapes, regional scenes of nature and countryside carefully observed and transcribed with both precision and verve.

For the current exhibit, Taft has continued in the latter mode. His panel paintings here have a remarkable sense of clarity and luminosity with a subtle painterliness inflecting a typically crisp delineation of receding areas of land and water. Skies are often smooth and their light infuses the whole scene. Cayuga Lake is often visible in the distance. An orange underlayer often peeks through the paint application.

Lansingville Road, a larger panel piece, is particularly striking. A smoothly painted pale blue sky—tinged with yellow—spills down more than half way while a distant hillside in impressionistic pale purples stretches down nearly to the bottom edge. The foreground is defined by a copse of trees, silhouetted in black and rising to touch the sky near the center. These have been accented in a faint blue, suggesting not so much highlighting as haunting. Taft likes to play with the idea of a foreground plane—here as elsewhere, the bottom edge sports a flat band, which on closer inspection, turns out to be a roof.

White Barn is a jaunty winter scene on small panel, memorable for the crisply defined miniature building that anchors its lower right corner.

Although not evident from the focused selection here, Taft’s wide-ranging body of work is interesting as a bridge between modernism and postmodernism: two cultural world-views apparently no longer on speaking terms. His most basic stylistic approach is in the tradition of a sort of modernist realism—in addition to the great French Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne, it recalls the careful, rigorously empirical work of the 20th century British painter William Coldstream and his followers. But there’s also another side to his work: an idiosyncratic eclecticism of style and subject matter as well as an—often literally—oblique approach to narrative.

That I tend to be skeptical of such approaches is well known—still, it might be interesting to see some of this more “difficult” work outside the campus setting.

This Friday, July 15 from 5 to 7 p.m., Corners Gallery will be holding a reception for both artists.